Over the past few years, I’ve led growth product teams focusing on retention and growing daily active users (DAU). Working on a myriad of challenges aimed at widening access to a global audience has deeply reshaped my understanding of inclusivity and what it truly means to build for a global audience and leave no one behind.

For a long time, I had a narrow view of inclusivity. I saw it as a nice-to-have, rather than a holistic principle that should influence many engineering decisions. Through experience, I’ve learned that even well-intentioned technical trade-offs can unintentionally exclude certain potential users.

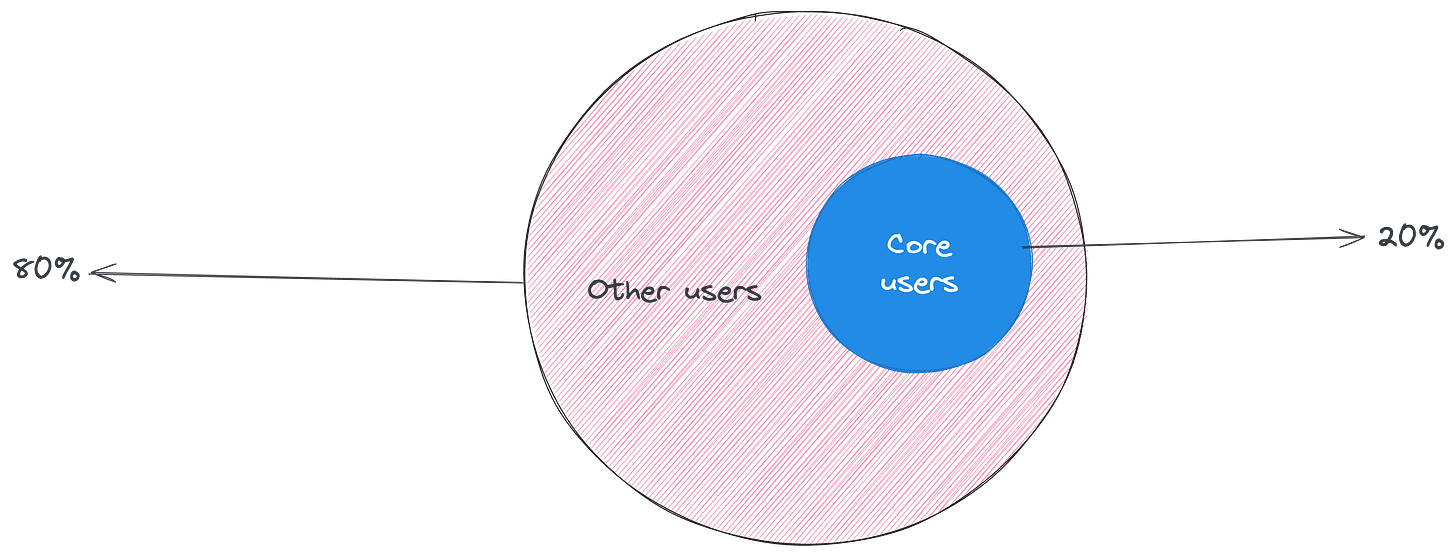

Think of it. Most products start small. They begin as simple ideas, gradually evolve, and eventually find market fit. At that point, the business identifies its core users—the cohort that drives the most value and gives the most feedback. Naturally, the focus shifts toward serving them better.

Teams start listening closely to these users’ pain points, prioritizing them, building new features to address their needs, and tailoring the product experience to them. This approach often feels smart and efficient. After all, it follows the familiar “80/20 rule”—what 20% of effort can deliver 80% of the impact?

It seems like a no-brainer to prioritize the 20% of users who drive most, or should I say 80% of the revenue. But over time, this focus creates an unintended consequence: the remaining 80% of users are quietly left behind. They’re excluded.

They might still show up occasionally—out of curiosity or necessity—but each time they do, the product feels a little more distant, a little less for them. The product speaks a quiet truth: “I know you need me, but I wasn’t really built for you.”

Too often, we default to “design and build for core users” or for users with fewer constraints because it promises better ROI. But the deeper, more important questions are:

-

What’s standing in the way of users who should be using your product but aren’t?

-

Are your design choices excluding people before they even have a chance to become “core users”?

Throughout my career, I’ve often heard (and said) statements like:

“Let’s prioritize the core users who matter most.”

At face value, these statements seem reasonable—and in many cases, they are. Prioritizing core users often feels like a sound, data-driven decision. But it becomes problematic when the entire development process is optimized solely around these users. Over time, the product begins to diverge, unintentionally excluding minority or edge users. The deeper we go down this path, the more self-reinforcing the cycle becomes.

The Engineer’s Bubble

It’s not just in product decisions; it applies equally to engineering. The context we live in profoundly shapes how we build, how we think, and how we perceive reality.

I’m reminded of a story from one of my German classes. It described how everyone is born wearing an invisible pair of glasses through which they view the world. Some have red lenses, others blue, and so on. Each pair of glasses colors our perception—what we see feels real and objective, but it’s deeply shaped by our lens.

The same is true for us as engineers. We build from within our own cultural and technological bubbles, assuming our experiences and environments are universal—but they’re not. Our daily context is one of privilege:

-

We use high-end laptops and modern devices.

-

We work with fast, reliable internet and constant power.

-

We test our applications on the latest browsers and operating systems.

-

We are early adopters of new technologies and easily embrace change.

A few years ago, when React was becoming mainstream, my team was thrilled to migrate our legacy app to this shiny new framework. We couldn’t stop talking about how much better the developer experience would be—faster builds, cleaner code, modern patterns. We imagined the productivity gains and the delight of finally using something elegant and efficient.

We rebuilt core parts of the product, added sleek new features, and gave the UI a fresh, modern look. Everything ran beautifully in Chrome, Firefox, and every modern browser. I remember thinking to myself, “How could anyone not love this?” I couldn’t wait for customers to experience it.

Then we launched.

We checked the logs and usage metrics; excitement quickly turned to confusion. Adoption was down, and a sizable portion of our users weren’t making it past the first few screens. What went wrong?

It didn’t take long to find the answer. It was Internet Explorer. They were using that specific browser. We had tested on every major browser except Internet Explorer. Some of our users were still on IE 8 and 9. The app broke completely for them.

We had assumed, without question, that “everyone” used modern browsers by now. But we were wrong.

That experience was a wake-up call. It reminded me that our reality as engineers is not the same as our users’ reality. The tools, devices, and networks we take for granted are luxuries many don’t know or have access to.

A large portion of the world still uses entry-level devices with limited processing power. Many experience intermittent connectivity or rely on expensive, slow internet in their day to day. When we’re not aware of this reality, our products become less and less usable to certain users who should be using them.

Inclusive product engineering is about widening access. It’s about being intentional in how we design and build software. It’s about writing code that runs efficiently and work for all users. It’s about optimizing yours so it has low battery, data, and memory usage. It’s about making sure no one is left behind.

With constant pressure to ship features quickly, inclusive software design can sometimes feel expensive or time-consuming. But the truth is, inclusion doesn’t always require much from the start. It requires more awareness, discipline, and intentionality from us.

How can you start making your product more accessible to the world?

Start with awareness

-

Begin with questions, not code. Challenge assumptions early and often.

-

Support accessibility from the start.

-

Who are you building for, how diverse are they, and how do they engage in the digital world?

-

Who might this exclude?

-

If you’re improving an existing feature, where are users dropping off—and why?

-

What happens if the user has a slower device or poor connectivity?

Test your product under different constraints

Just as automated tests shouldn’t stop at the “happy path,” feature testing shouldn’t either.

-

Throttle network speeds to simulate unreliable internet. Does your app handle it gracefully?

-

Test on older, entry-level devices or budget phones.

-

Use accessibility tools like color-blindness simulators or voiceover modes to check usability.

-

How does the app work with LTR and RTL languages?

Design and code with constraints in mind

-

Use lightweight assets and reduce dependency on heavy libraries.

-

Prioritize clarity and the primary jobs users need to get done.

-

Respect data-saving mode in your code.

Involve diverse voices early

Encourage your research and design teams to broaden their participant groups and ensure diverse representation.

If that’s not possible, ask for feedback from teammates in different regions, on different devices, or with different cultural perspectives. Even small variations in context can surface assumptions you didn’t realize you were making.

In conclusion, focusing on the “core 20%” might feel efficient in the short term, but it risks alienating the very users who could expand your product’s reach and impact. As engineers, our code shapes the world. Making the world more equitable begins by stepping outside our bubble, questioning our assumptions, and designing for the full spectrum of users—not just the ones who look, think, or live like us.