Twitter users tweet 500 million tweets per day. The volume of information going through Twitter per day makes it one of the best platforms to get information on any subject of interest. In this post, I’ll walk you through how I built a Twitter bot with a brain.

According to a report, there are 48 million bots on Twitter — and hubofml happened to be one of these bots. Hubofml started as a simple bot written in Node.Js (on one Sunday evening) running on a free Heroku dyno that tracks specific hashtags like machinelearning, computervision, and retweet tweets containing those hashtags.

My goal was to use the bot to collate information on machine learning and re-broadcast to people interested in them — after all, some of the best posts I read on machine learning came from links shared on Twitter by the community.

I thought it would be cool to have a bot that tracks hashtags related to machine learning that I follow to stay informed.

Days after the bot was deployed, I started noticing some forms of abuse and spam like this:

People would write tweets unrelated to machine learning and hashtag “machinelearning,” and the bot would retweet it.

When we think of spam, it’s easy to see them as unsolicited emails one receives from an unknown person.

As odd as it may seem, spam is not limited to emails alone these days. Spammers now target everything you can think of. From your inbox to comments on social media posts, you’ll find spam lurking around.

Personally, I think spam is destructive to communication and undermines the goal of social media.

For the rest of the post, I will focus on how I used text categorization to combat spam on Twitter.

Text categorization is the process of automatically assigning one or more predefined categories to a text document. It has a wide range of use cases like articles categorization, spam detection, intent detection, etc.

As I proceed, if you like to take a look at the Jupyter notebook I used for this task, you will find it on Google colab here or in this repository.

Getting Twitter Datasets

There are four ways to obtain Twitter public data. Justin Littman wrote an impressive article on the four approaches.

For this task, I used the free (Twitter Standard) APIs. I downloaded about 110k of tweets datasets from Twitter using a python library called Tweepy.

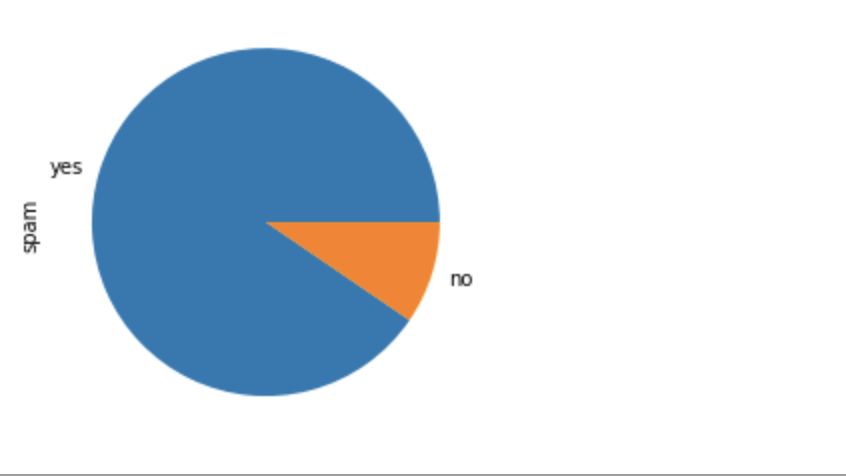

I annotated the datasets using two labels: “yes” and “no.” All spam tweets were labeled “yes” and non-spam tweets were labeled “no”.

Spam tweets (in this context) are tweets with no context to the field of machine learning. They are usually about politics, crime, religion, trolling, etc. I retrieved spam tweets based on randomly selected keywords from Wordnet as hashtags.

Non-spam (Ham) tweets are tweets related to machine learning, computer vision, NLP, etc. I collected non-spam tweets by tracking hashtags like machinelearning, computervision, NLP on twitter using the Tweepy library.

Data Exploration

My next step was to accrue some knowledge about the data and its nature after downloading the datasets. The datasets contained 99,989 tweets labeled as spam and 10,538 tweets labeled as non-spam.

Spam vs Non-spam

The data distribution between the two labels shows that the tweet datasets are highly unbalanced. Unbalanced datasets often have substantial effects on how machine learning models generalize. The model could learn that spam tweets are more predominant, making it natural to lean toward the predominant class during generalization.

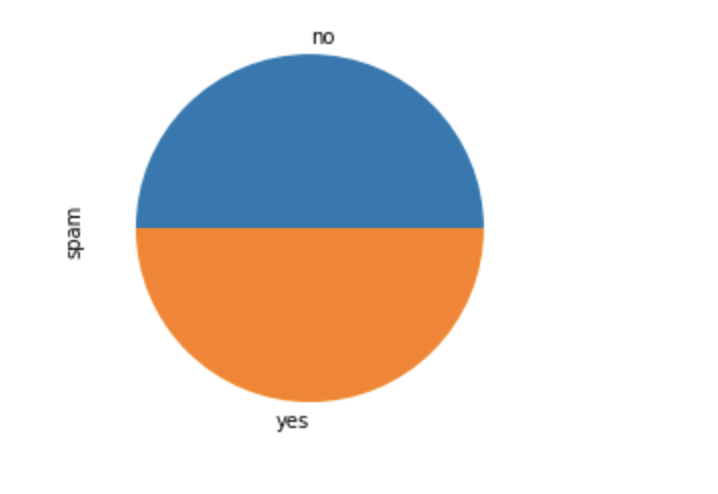

I downsampled the majority class to arrive at an equal number of spam and non-spam (ham) tweets, 10,000 tweets in each class, accounting for a total of 20k tweets in the downsampled dataset.

Spam vs Non-spam

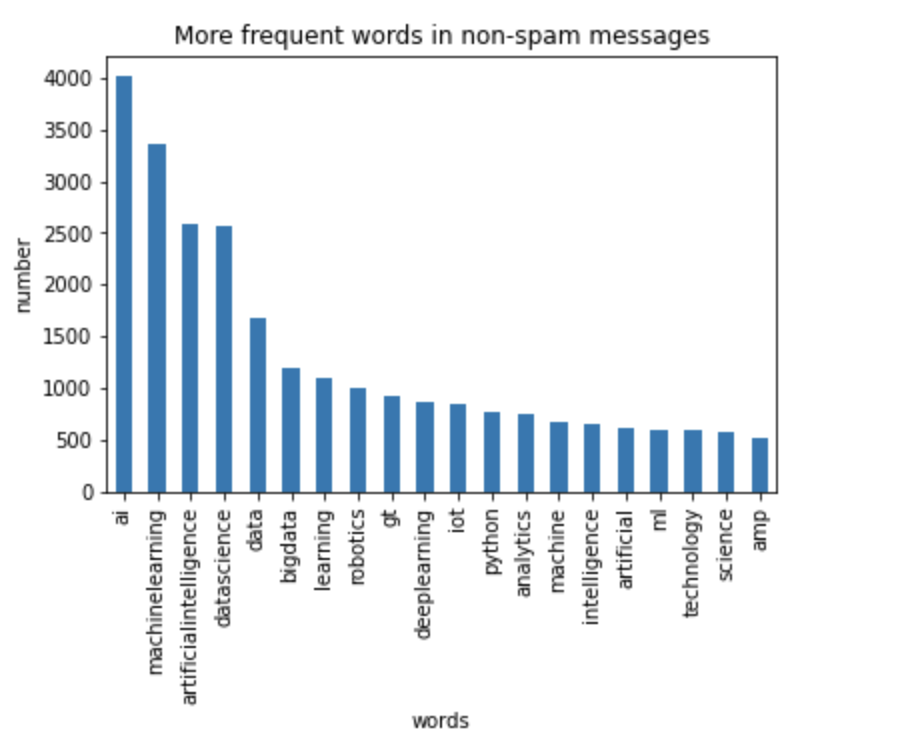

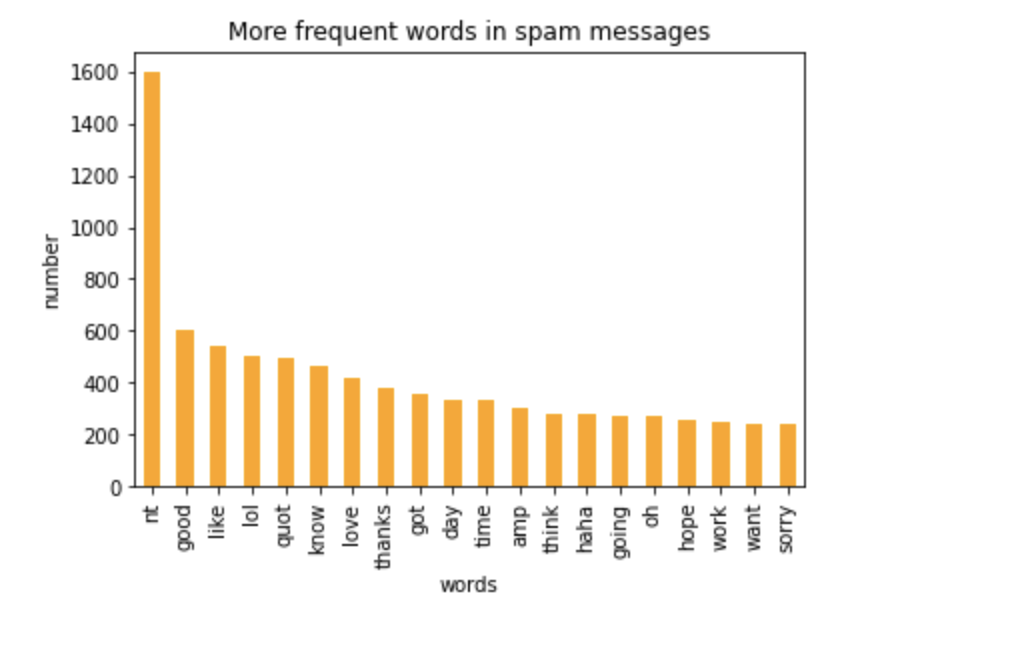

To get further insight into the data, I plotted the top-10 most common words in the two classes. For the non-spam tweets, ai, machinelearning, artificialintellgience, data, data science, biodata, python, and deep learning were found to be most common, as shown in the figure below.

On the other hand, words like good, lol, like, thanks, day, know, and sorry were found to be most common in spam tweets.

Data Preprocessing

Like text documents, tweets are not exempted from noises. This is, as a result, no formal way of representing tweets. Tweets contain certain special characteristics, such as usernames and retweets, signified by “RT,” links, emoticons, and unimaginable things.

It’s essential to clean them up before fitting a model. I applied several preprocessing steps like lowercase conversion, URLs removal, usernames removal, emoticons removal, tokenization, and stemming.

In addition, tweets also contain common words that are of little value to the context of the text. These words are known as stop words. Stop words are a set of commonly used words in any language. Hence the removal of stop words from tweets was crucial to focus on the important words in the tweet.

Feature Selections

Vocabulary list

A vocabulary list is a dictionary of words having each word in the dataset as a key and the number of times they occurred as value.

A vocabulary list could be:

{"machinelearn":100, "Trump":10, ""}

I built a vocabulary list of all words, excluding stopwords and words with less than 2 occurrences in the datasets.

Tweet Vectorization & Padding

Machine learning models take vectors as input. In order to perform machine learning on text documents, we need to transform text documents into vector representations. This is known as text vectorization.

In my approach, I assigned a unique number to each word the vocabularies. Each tweet is encoded using the unique number assigned to the word. If a word could not be found in the dictionary, it’s automatically assigned a value of 1 — a value reserved for words that were not found in the vocabulary list.

Given the following vocabulary list:

{ "The": 5, "cat":1, "sat":3, "on":4, "mat":2, "in":6, "unk":0}

A sentence like “The cat sat on the mat in the morning” will be encoded as [5,1,3,4,5,2,6,5,0 ].

Finally, I used pad sequence to convert the variable-length sequence to the same size. This is crucial for the network to take in a batch of variable-length sequences.

Dataset Splitting

I split the datasets into training and test set. A training set is used in learning (fitting the model) and a test set for testing how the model generalizes on unseen data. 60% of the dataset was used for training, and 40% was used for testing.

Model Architecture

In the past few years, there have been many groundbreaking successes from applying RNNs to a variety of problems: speech recognition, language modeling, translation, image captioning, etc.

RNNs are great, but they suffer from short-term memory. If a tweet is too long, an RNN might have a hard time carrying information from earlier time steps to the current time step.

I used an LSTM network, a variant of RNN. LSTM avoids the long-term dependency problem by remembering information for long periods. They have internal features called gates that regulate the flow of information in and out of the cell state. There’s an interesting article on LSTM if you want to know more about how it works.

The network architecture consists of three layers, and it’s bidirectional. A bidirectional network allows inputs to be processed from the first to the last and from the last to the first. This ensures that the network is able to preserve information from both the past and future.

The first layer is the embedding layer, which transforms the input vectors into dense embedding vectors.

The second layer is the hidden layer, which takes in the dense vector and the previous hidden state to calculate the next hidden state. The final layer takes the final hidden states and feeds them through a fully connected layer, transforming it to the correct output dimension.

You can find more on the architecture in the Jupyter notebook.

Deployment & Inferencing

After training the model, I deployed the model artifacts using Flask to Heroku free dyno for real-time inferencing.

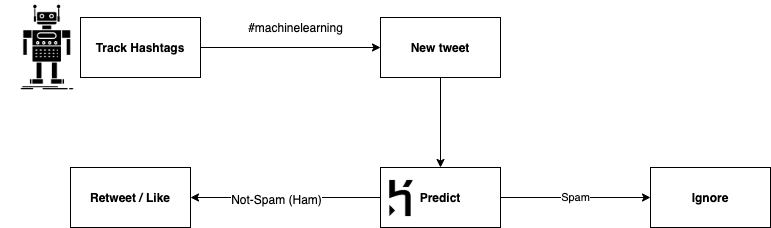

From tracking tweets to retweeting or liking, the communication process looks like this:

- Bot finds a new tweet on machine learning

- Bot calls the Heroku endpoint to predict the class of tweets.

- Non-spam tweets are retweeted/liked while spam tweets are ignored

Conclusion

While the model performed beyond my expectation, however, it’s far from being accurate. Occasionally low-quality tweets still manage to escape the spam filter. I believe that could be improved by using quality datasets.

The tweet datasets I used for this task were in tens of thousands; there were tweets with wrong labels. This can be improved by crowdsourcing the labeling task using services like AWS Mechanical Turks.

This is my first attempt at combating spam on social media, and I do hope to take this work further in the future.

Every month, I send out a newsletter containing lots of exciting stuff on data science, software engineering, and machine learning. Expect quick tips, links to interesting tutorials, opinions, and libraries. Subscribe here